- Home

- Gretchen Olson

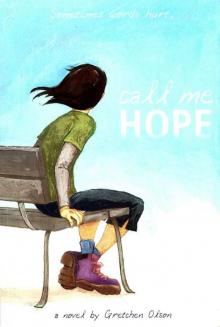

Call Me Hope Page 3

Call Me Hope Read online

Page 3

“Is sixty points a lot?” asks Joshua. “It sure is,” says his father. “And if you stay hidden all day it’s a hundred and twenty points.”

Every time I feared for Joshua’s life, his father came up with a clever plan. Every time Joshua questioned the game or repeated horrible rumors, Guido zipped out a perfect answer or awarded more points.

Thank you, I thought, wishing Guido could hear me. You are an amazing father.

At the end of the movie, the United States Army is coming and the Germans are madly pushing Jewish prisoners into trucks, hoping to get rid of a few more loads. Guido is frantic. He quickly hides Joshua, urging him not to come out of the small cupboard, telling him they’ve earned a thousand points and they’ve won the grand prize, the tank. Then he’s off again, disguised as a woman, racing to find Dora, madly searching, calling, then shouting at her to escape from the departing truck. As he’s warning her, he is discovered and captured. A Nazi soldier marches him to a nearby alley. They disappear into darkness.

A gun fires.

Oh, no! Tears filled my eyes and fell to my blank paper.

The concentration camp is deserted. Quiet. Fires burning. Hidden prisoners begin appearing and Joshua comes out of his cupboard. All of a sudden, a U.S. tank comes around the corner and Joshua’s eyes grow huge. “It’s true!” he says. The tank stops right in front of him and out pops an army guy speaking English. “Want a ride?” he asks Joshua.

Everyone in the classroom started clapping. My throat tightened and my eyes blurred.

As the tank follows the road lined with departing prisoners, Joshua spots his mother in the crowd. “Mama!” he cries, and the soldier lowers him into his mother’s arms. They sit alongside the road, hugging and kissing. “We won!” Joshua announces. “We came in first!” Then a man’s voice tells us: “This is my story. This is the sacrifice my father made. This was his gift to me.”

I shivered and realized Mr. Hudson had turned off the TV. The room was still dark but I could see him leaning against the TV cart, his head bent. My nose dripped but I didn’t move to wipe it. Someone sniffled, sighed. A cough.

“I’m sorry.” Mr. Hudson gently touched the silence. “I didn’t plan this very well.” He glanced at the clock. “The bell is about to ring and something this serious deserves more time. You’ll probably feel a little strange going home with kids who have no clue what you just went through. Stay focused, if you can; try to remember what you saw; let it sink in; think about the questions; talk with your parents, as they allowed you to see this film.”

The bell rang but no one moved.

Slowly, one by one, kids began shuffling their chairs and standing up.

Someone turned on the lights. I squinted and met Noelle’s watery eyes. Justin walked to the door staring at the floor. I didn’t want to go home; I wanted to rewind the film and stop at a happy spot, before all the hurting and pain.

CHAPTER 6

Next to New

Why did it always rain when I had to walk home? I trudged away from school, hoping Anne Frank wouldn’t get wet in my backpack. Not that I had miles to go, but it was a good fifteen- to twenty-minute fast walk. I wasn’t in any fast mood, though. Not after that movie. I kept thinking about Joshua and his mother and what I’d give for that kind of reunion. I could still hear his excited voice: “MAMA!” Maybe my mother would miss me if I was lost in the woods or held hostage in a bank robbery. “HOPE!” she’d shout as I raced into her arms.

I’d just passed Eola Hills Pizza and Coastal Bank, staying dry beneath their awnings, when I saw the boots. They were purple. Well, mostly purple, with some brown and green designs. The bottoms were thick black rubber. There I stood, nose pressed to the window, my breath washing the cold glass, my heart craving those beautiful boots.

I barely noticed the yellow ski jacket and red back-pack in the Next to New display. Actually, I’d barely noticed the store before. Mom said she’d never set foot in one of those musty-smelling consignment shops, let alone in someone else’s shoes. But these boots looked brand-new and I could just see myself in them at Outdoor School.

A bell jangled as I opened the door. I braced myself for knockdown body odor and an instant skin rash, but nothing happened.

The woman behind the cash register smiled.

“Could I try on the purple hiking boots?” I pointed to the window display.

I sat on a bench and slipped off my tennis shoes.

The woman handed me the boots. Her name tag said “Anita — Owner/Manager.” I quickly put them on, winding the leather laces around the top hooks and tying a thick bow. Oh, man, did they feel great. I stood and looked at Anita. She pushed her glasses into her orangish hair, examined my feet, and announced, “Awesome.”

They were heavier than I’d expected, but they made my feet feel strong. Same with my legs. I could march across the country, or at least across Oregon. For now, I walked around the store, weaving in and out of dresses, pants, jackets, baby clothes, and wedding gowns. I stole glances into the full-length mirrors, trying not to smile at cool me, taller me.

I bent over to check the price and wished I hadn’t: $14. All I had was $5.45 sitting in a glass jar in my top dresser drawer.

I hiked over to Anita, now laughing and sorting through a pile of clothes with another name-tagged lady: “Ruthie — Asst. Manager.”

“How do you pay for things here?” I asked. “I mean, can I put these on layaway?”

Ruthie inspected my feet. “You can pay for those gorgeous boots by letting us sell your nice, outgrown clothes.” She handed me a flyer: Welcome. We’re pleased you want to be part of our clothing family. Here’s how it works.

I was to wash and iron my clothes, place them on hangers, and bring them to the store. I’d receive forty percent of the selling price. My mind shot through my closet and drawers. Jeans, too small. T-shirt with teddy bears and valentines, too babyish. There was a lot of stuff crammed in the back of my drawers and under my bed.

“To hold the boots,” said Anita, as if we were about to close a big business deal, “you’d need to give us twenty percent of the price. That would be two dollars and eighty cents.”

“No problem. I’ve got that at home. I’ll bring it right back. Please don’t sell them while I’m gone.”

As I tugged the boots off, she added, “The rest needs to be paid in two weeks.”

Two weeks!

“Otherwise,” she added, “you lose your down payment.”

“How soon will my clothes sell?”

She shrugged. “You never know, but bring in winter clothes now and save your spring and summer things for later.”

I jogged most of the way home, jumping puddles, imagining myself in those amazing boots at Outdoor School, leading the trek up Lava Butte.

I stopped at an intersection to catch my breath. Leaning against the streetlight, I felt my heart throbbing in my neck. It was a good throbbing, though, not a bad throbbing like in Mrs. Piersma’s office that morning. But she’d been extra nice after Mom had left. “Are you okay?” she’d asked, handing me two pieces of candy.

“Yeah,” I’d said, stuffing them in my pants pocket. Icould live here in your office, eat peppermint candies, and have happy thoughts. I’d never have to ride the bus again and I’d always be on time.

“Come visit me again, Hope,” said Mrs. Piersma, “just for fun.”

Since when did you visit the principal just for fun? And why did she sound more sad than happy?

The sky had turned dark now with another rain cloud. Car headlights glowed in the road spray. I shivered and started jogging again. Better get home before Mom. Not that I was doing anything wrong, but there were always questions and she definitely wouldn’t like the Next to New business. I’d have to hear all the reasons why I shouldn’t even open their door.

My heart sank as I turned up our driveway and saw Mom’s car in the garage. I fumbled in my pocket for a peppermint.

“Where have you been?” Mom stood in

front of the open refrigerator, her back to me.

“I had to walk, remember?” I knew it was smarty to remind her, but I couldn’t help it. My feet were freezing.

She jerked around, a plastic bottle of mustard in her hand, the nozzle pointed at me. I could imagine mustard splattering all over me and the kitchen and I couldn’t help smiling.

“Wipe that nasty smirk off your face right this instant.” She shook the bottle at me. “Your punishment was to stay in your room tomorrow. Now it’s the whole weekend, starting right this minute!”

“But I wasn’t smirking. It was just funny seeing you shake the mustard bottle.”

“You dumb shit! Don’t you dare talk back to me!”

“I’m not.”

“Don’t argue.”

“I’m not. Can’t I come out at all?”

“You can go to the bathroom and eat in the kitchen. That’s it.”

“What about the laundry room? I gotta wash my clothes.”

“So wash them.”

“And dry.”

“FINE.”

“Iron?”

“SHUT your stupid mouth UP!” She slammed the mustard on the table. “God, girl, you really know how to push. Get out of here — right now.”

My boots! I had to tell Anita I wasn’t coming back. “Just one phone call.”

“No calls.”

I went to my room and fell onto my bed, my cold bare feet sticky against the comforter. Shut up! Shut up! Shut up! I said the words out loud, face crammed into my pillow, but my entire body ached to scream them as loud as my voice could carry them; right out my door, down the hall, into my mother’s face. Why not? She said them to me.

CHAPTER 7

A Secret Place

I stood at my bedroom window and stared into the black night. Rain splattered against the glass and cold air slipped past the rattling wood frame. Maybe I should just open the window, slip out, and find a new life. It was an exciting thought, a huge relief, but one that should have a plan. Besides, I’d had enough wet feet for a while and I did have plans — not big ones like running away, but busy ones to keep my mind off Mom and the purple boots.

Plan A: Change into Dry Clothes. Sweats and slippers.

Plan B: Clothes for Next to New. I opened my dresser drawers one by one, took everything out, and laid them on my bed according to: 1) Save for me 2) Sell at Next to New 3) Give to Goodwill. Underwear, T-shirts, jeans, shorts, socks. Some of the stuff, like my rainbow pajamas, I hadn’t worn in years.

I did the same thing with my closet clothes, getting rid of little-girl dresses, short skirts, blouses that un-tucked, wornout belts, and outgrown shoes. One final place: under my bed. Ugh. Scrunched clothes smothered in dust bunnies.

I like our laundry room. It’s small and tidy — shelves for soap and bleach; baskets for ironing, mending, and rags; drawers with sewing supplies and wrapping paper. When I close the door and turn on the ceiling fan, I feel like I’m in charge: full load, one scoop soap, hot wash, cold rinse, extra spin. Check, check, check. All systems go.

I pushed Start. Water rushed against the metal tub. The laundry room echoed with a chorus of hum, drum, whirl.

Now I was in a cleaning mood. Without being told, I gathered rags, paper towels, Endust, and Windex, and headed back to my bedroom prison. Starting with my dresser, I went around the room spraying and wiping furniture, windows, and the mirrors on my closet sliding door. I even dusted my stuffed animals.

Plan C: My Closet. All this digging out and cleaning up made me think of Anne Frank and her family settling into their hidden “Secret Annexe,” with the unpacking of boxes, sewing and hanging of curtains, scrubbing of floors, and decorating of walls, all to make it feel safe and normal.

With my next trip to the laundry room, I brought back extra blankets, a pillow and pillowcase. I stretched my bedside lamp into the closet and arranged the bedding in there. I lined all my stuffed animals along the back. Then I taped a newspaper picture of Gabriela Feliciano to the wall. Turtle sat on top of my pillow, and Anne Frank’s diary lay on the blanket.

“Dinner’s ready.” Mom’s voice approached. I jumped out of the closet and shut the door just in time. The bedroom door swung open and she examined the piles on my bed.

“I — I decided to wash everything,” I said, avoiding her eyes.

“That’ll keep you busy this weekend. You can do mine when you’re done.” She laughed like it was a joke. “Seriously, Hope, your room looks great.”

My eyes shot to hers. Yes, they were smiling, along with her mouth. Wow. My face heated and I tried not to smile back, but I couldn’t help it. Now maybe she’d visit every day and tell me — in a light, sunny voice — “Hope, your room looks great. You look great. You have great ears and a great nose and eyebrows and —”

“Wash your hands. They’re filthy.”

We sat across the table from each other, eating spaghetti. Flowers and a funny birthday card decorated Tyler’s place. He’d given them to Mom, wished her happy birthday, then left for Egan McGowan’s for the night. Smart guy.

Mom looked relaxed in her baggy Detroit Lions sweatshirt and flannel pj bottoms, no earrings, hair pulled back into a ponytail, makeup washed off.

She let out a huge sigh. “I can’t tell you how stressed I am.”

I concentrated on twirling noodles around my fork.

“I race off to work, put in a long day, stop by the grocery store, fix dinner, harp on you two to do homework, iron my clothes for the next day.” She took a bite and I wondered if we’d ever have a different conversation.

“Are you listening to me, Hope Marie? Have you heard a single word I’ve said? Look at me when I’m talking to you.”

I looked.

“Repeat my last sentence.”

I hate the listening test. It always comes when you’re not listening. “Look at me when I’m talking to you,” I said, immediately regretting the wrong answer.

Mom’s mouth tightened and I imagined a rattlesnake’s tongue flicking out of her mouth, ready to strike. She dropped her fork into her spaghetti, crossed her arms on the table, and glared.

I felt the prick of tears but fought them back. As a little girl, I’d cried at my mother’s angry face and stabbing words, but over the years I’ve tried to block them from my ears and from my gut, where they turned to inside tears. It doesn’t always work, though. I just wished I understood how she could be so nice one minute and so angry the next — like she was two different people.

“My advice to you, young lady,” Mom said, with her fork pointing at me, “don’t get married and don’t have kids.”

With that bit of wisdom stuck in my brain and French bread stuck in my teeth, I returned to the laundry room. I plodded through another wash/dry cycle, folded clothes that were staying, sacked Goodwill stuff, and hung out clothes to iron. When I crawled into my closet that night, I was exhausted, but not so wiped out as to miss the sweet peacefulness drifting down… floating across my bed, my pillow, Turtle, and me. There, in my narrow, dark closet, with the sliding door barely opened, I felt strangely safe and happy. I hugged Turtle, settled into my pillow, and thought about my purple hiking boots. I could see the heavy, thick soles; I could smell the outdoors; and I crossed my fingers they’d still be there Monday.

CHAPTER 8

Number the Stars

The next morning I awoke still holding Turtle, neither one of us having moved an inch all night. I looked straight up, into the uneven shadows of dresses, skirts, blouses, and pants. After all that sorting, washing, and cleaning business yesterday, these leftover clothes seemed like old friends.

Mom was still asleep and Tyler was still at Egan’s. I like having breakfast by myself. I can fix whatever I want without anyone eyeing my every move, telling me I shouldn’t cook the eggs so long or that I should toast the bread longer. That morning I made fluffy scrambled eggs, golden brown toast, and a pitcher of orange juice. When I was done eating, I cleared the table, put everything away,

loaded my dishes in the dishwasher, and wiped sticky juice drops off the floor. Surely Mom would notice how clean I’d left things and then she’d drop the rest of my punishment.

I started another load of laundry and was folding clothes when Mom opened my bedroom door. “Don’t ever take the last eggs. Someone else might want them, too, you know.” I started to tell her about cleaning up, but she slammed the door. I opened it after her. “Can I iron in front of the TV?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

She spun around. BIG SIGH. “Today is Saturday. I’ve worked hard all week and I need at least one day of peace and quiet. So don’t bug me or I’ll make it two weekends.”

I closed the door, leaned against it, and inspected my room — the walls, the window, my swivel chair, desk, and star chart. Five hundred stars. That’s what this punishment should be worth. I closed my eyes and imagined myself flying like a bird, free to go wherever I wanted, high above snowy mountains or skimming low across the ocean to a tropical island with palm trees and pineapples. Or into a sparkling night sky, dancing from star to star, making my own pattern: the Hope Constellation.

Suddenly I saw Joshua in the concentration camp, stamping his foot and telling his father he wanted to go home. “They’re mean here. They yell.” I’ll bet his father wished he could have flown Joshua away, but instead he created the clever point system for distraction, for the real army tank.

Problem Solve: I needed a distraction. And a prize. I deserved a prize for all the hours in this room. A prize for my mother’s sighing and glaring, for “stupid,” “brat,” and “dumb shit.”

That’s when it hit — a great idea, a great distraction. I hurried to my desk and looked through the drawers, finding a little spiral notebook with a black Lab puppy on the front. On the first page I wrote “HOPE’S POINT SYSTEM.” After lots of writing, crossing out, erasing, and rewriting, this is what came out:

Call Me Hope

Call Me Hope